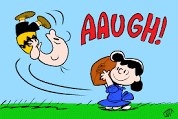

“So, we need to slice and dice those users by age, household income, geography, gender, eye color, and Zodiac sign. And can we get 50 of each? And they’ll need to do all 63 tasks in that email I sent you 10 minutes ago. Oh, and can we get a full report by tomorrow?”

You know, sometimes it’s best if the user researcher leads the research effort. I don’t know. Just an idea. Might work.

I must admit, this only seems to come from folks who are brand new to usability. You know, the people who think usability testing is QA, or a focus group, or a marketing survey, or a combination of all three, or whatever.

So, education is definitely key in these situations. How to go about that though?

I’m always tempted to just say I’ve been doing this for 35 years, stopped counting at 4,000 users, and actually know what I’m doing. So, just shut up and let me do my job!

Now, that would be fun. There are, though, a couple of things that are a little more realistic that I’ve found particularly useful over the years.

For one, if there are some unfamiliar names and faces in the meeting, is simply to ask if everyone’s familiar with usability research. If not, I can head a lot of this sort of thing off at the pass by giving a nice, simple, accurate definition.

Another is to make sure I’m not alone. In other words, ensure that there are some people at the meeting who do know what a usability test is. Encourage them to pipe in. If they’re higher up the food chain than you, have them preface the meeting with a few words. In other words, feel free to gang up on your troublemakers. There is strength in numbers.

And if it really comes down to it, my trump card is to ask, in the politest way possible of course, how they would feel if I were to create their wire frames for them, or write their content deck, or make their GANTT chart. We’re all professionals here, right?